Mob Lynching in India

December 5, 2018 | Expert Insights

Inspector Subodh Kumar and a local youth were killed in Uttar Pradesh's Bulandshahr when a mob went on a rampage over allegations of illegal cow slaughter. The officer was the investigating officer in the Akhlaq lynching case of 2015.

Background

In 2015 a mob lynching occurred in which a mob of villagers attacked the home of a Muslim man Mohammed Akhlaq, whom they suspected of stealing and slaughtering a cow-calf in Dadri, in the Indian State of Uttar Pradesh. 52-year-old Mohammad Akhlaq Saifi died in the attack, and his son was seriously injured. Lynching is the informal public execution by a mob who wish to punish an alleged transgressor or to intimidate a group. In India, lynching generally arises due to tensions between two cultural groups, and as a result of fake news proliferated over social media, especially WhatsApp. Between May to July 2018, at least 25 people were killed in mob lynchings across the country.

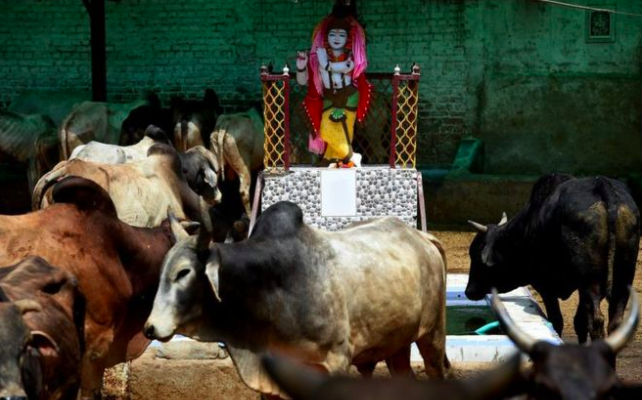

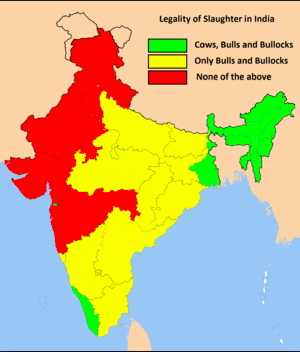

On 17 July 2018, India's highest court asked the government to enact a new law to deal with the increase in mob violence and lynchings that had reportedly killed more than two dozen of people in the country. The Supreme court was hearing a number of petitions seeking direction on checking mob violence by vigilantes targeting Muslims over suspicions of beef consumption and cattle slaughter. Fatal attacks had been carried out on Muslims by “cow protection groups" who have roamed highways, inspecting livestock trucks. India's Hindu majority regard the cow as holy and their slaughter is banned in several Indian states.

Since 2014, there have been increasing incidents of mob violence and lynchings targeting Muslims and Dalits, for whom beef and buffalo meat is a staple food. Since the end of April 2018, more than two dozen people were beaten to death by mob vigilantes across India over suspicions of child abduction. Activists and technology analysts have raised alarms that messaging applications like WhatsApp are being hijacked by people intent on spreading hoaxes. WhatsApp is a free app, which runs even on low-priced phones, making it easier for messages to spread among the country's millions of consumers.

Analysis

Two people, including a police officer, have been killed in northern India during violent protests by villagers over suspicions of cow slaughter on 3 December in Bulandshahr, India. Inspector Subodh Kumar was shot dead in the Bulandshahr clashes; he was investigating officer in the Akhlaq lynching case that stunned the nation in 2015, and had arrested some of the accused who were involved in the brutal killing of Akhlaq.

The mob attacked the local police station and set it on fire while also attacking the police officer. An eyewitness said Inspector Subodh Kumar could have been saved but the agitators didn’t let the policemen take Subodh Kumar to the hospital.

Police say the area grew tense when the carcass of a cow was found dumped in a forest area outside the Mhaw village. Right-wing activists soon gathered at the spot to allege that members of another community were indulging in cow slaughter, triggering tension in the area. Soon, they started raising slogans against the administration and police and turned violent. The mob pelted stones set the police station on fire and opened fire that killed two.

US-based rights group Human Rights Watch (HRW) has accused the government of failing to protect religious minorities and other vulnerable groups from frequent attacks.

Counterpoint

The ‘Not In My Name’ campaign was launched across India in June last year to protest against the wave of attacks on Muslims by mobs. Last year, more than 100 military veterans wrote an open letter to Modi, condemning the targeting of Muslims and Dalits, a lesser-privileged caste. The prime minister has publicly criticised so-called cow vigilantes and promised tough action against the perpetrators, but opposition leaders accuse the government of indirectly supporting the so-called Hindu cow vigilantes. UP CM Yogi Adityanath expressed grief over the deaths in violence in Bulandshahr and sought a probe report into the incident within two days.

Assessment

Our assessment is that India’s spate of mob lynchings is increasingly alarming and shows no sign of abating. We believe that the 27 such killings in the past year showed a similar pattern: helpless police often outnumbered by the mob, and the use of social media resulting in a larger, angrier horde. In our opinion, regulating social media platforms would not have any effect until the predisposition for violence and hate crimes are addressed at the source.

Comments