Farmers March on Delhi

December 1, 2018 | Expert Insights

Thousands of Indian farmers marched to the capital to demand that government bring in legislation providing a guaranteed minimum support price for their crops and freedom from debts.

Background

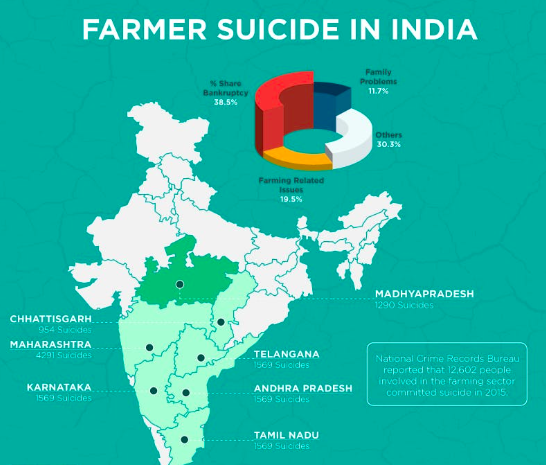

Farmer suicides in India, also known as the agrarian crisis, has been a problem for the country since 1990, caused by farmers inability to repay growing debt, often taken from local moneylenders and microcredit banks to pay for high priced high yield seeds marketed by MNCs and the non-implementation of minimum support prices (MSP) by central government and state governments. From 1998 to 2018, this has resulted in the suicides of 300,000 farmers in the country. 1,753 debt-ridden farmers have killed themselves since June 2017.

The years between 2015 and 2018 have seen several farmers marches across the country. In some cases, they have become deadly. In June 2017, police shot at a group of farmers in Mandsaur, killing at least six. In August 2017, farmers from the southern state of Tamil Nadu started a hunger strike in New Delhi's Jantar Mantar. Exasperated by what they viewed as government indifference, they escalated their protest by holding human bones and dead rats in their mouth, even threatening to ingest faeces if their demands were not met. When farmers protested in Delhi on October 2, they were met with barricades, water cannons and even tear gas shells.

Analysis

On 28 November, thousands of farmers, labourers, and rural workers from across India boarded trains and tractors to the capital to participate in a two-day "Dilli Challo" (Let's go to Delhi) march.

They marched to parliament on 30 November to ask legislators to tackle the many challenges facing agrarian society. They will demand the passing of two bills, one to relieve farmers from debt and the other to secure minimum prices for their crops. This is first time over 200 farmer bodies have come together to protest under a single banner. 100,000 farmers have reportedly arrived in the national capital and around 21 political parties have supported the march.

Farmers belonging to the Scheduled Tribe community Dhamangaon village in Maharashtra's coastal district of Palghar are attending the New Delhi event to protest the acquisition of their land for the 508km-long high-speed rail corridor connecting Mumbai with another state capital, Ahmedabad.

Others are participating in the march to demand a loan waiver, and a reduction in the prices of input material like seeds, fertilisers, and irrigation equipment. Another issue is the controversial change in the definition of drought by the central government in 2016. By measuring drought-affected areas on the basis of districts, rather than sub-divisions, the total number of drought-affected regions was brought down considerably on paper, and those affected are no longer eligible for relief.

The issue of farmer suicides, which increased by 42 per cent between 2014-15, is paramount. In 2016, the National Crimes Record Bureau stopped publishing farmer suicide rates, which some allege is an attempt to clear the government's track record. For the farmers, undertaking the journey to reach New Delhi involves tremendous sacrifice. This is because their absence will be acutely felt during the crucial harvest season back home.

Counterpoint

Following previous protest marches, the India Union minister of state for agriculture Rajendra Singh Shekhawat said the government was assuring the farmers to take forward their cause. The minister said the government would look at bringing in some changes to the minimum wage rules for rural areas to solve their minimum support price problem. "The government has formed a committee of six chief ministers to look into this issue of labour for the farm. The committee is in talks to connect MNREGA with agriculture," Shekhawat added.

On behalf of Union Home Minister) Rajnath Singh, he assured protestors that the farmers' interests would be represented in this committee and the changes that would be required to link MNREGA with agriculture will be made.

Assessment

Our assessment is that to address the agrarian problem in India, there is a need to go beyond the singular focus on “prices” and address fundamental structural reforms in the farming sector.

We believe that farm incomes have been unviable for a long time now, due to rising input costs and falling output prices, inequitable access to water resources and technological inputs, increasing and intensive cultivation of cash crops and a corresponding decline in productivity.

In our opinion, a consequence of the waiver of loans could be the demise of credit institutions.

Comments